Entangling telecom photons with quantum dot spins

A look at how telecom wavelength quantum dots could enable more efficient, long-distance quantum networks.

INSIGHT

Andrea Barbiero

7/13/20255 min read

Entanglement is a fundamental and fascinating phenomenon in quantum mechanics, where two particles become linked in such a way that the state of each cannot be described independently of the other, even when separated by large distances. Beyond its conceptual significance, the controlled generation and distribution of entanglement is critical for quantum information processing and quantum networking. But why do researchers use semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) to generate entangled photons? And why is it important to entangle telecom photons with semiconductor-confined spins?

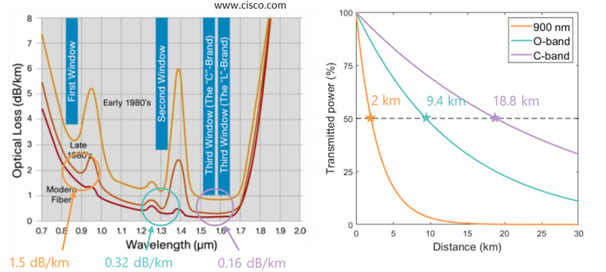

Long distance quantum communication, much like today’s classical internet, will rely on optical fibres. For practical and scalable implementation, it is crucial to leverage the existing commercial fibre infrastructure. However, standard silica fibres are highly sensitive to wavelength: photons at shorter wavelengths (such as around 900 nm) suffer significant attenuation, whereas photons in the telecom bands, around 1310 nm (O band) and 1550 nm (C band), experience much lower losses, making them ideal for long distance transmission. To illustrate this difference, a 900 nm signal loses half its intensity after just 2 km of fibre, while a 1550 nm signal requires 18.8 km to reach the same level of reduction. While frequency conversion techniques can shift visible or near infrared photons into the telecom range, they are typically inefficient, often incurring losses of around 50%. Generating entangled photons directly at telecom wavelengths avoids these conversion losses and enables a more scalable and practical path toward quantum networks.

Semiconductor QDs are among the best solid-state sources of indistinguishable single photons at telecom wavelength. Encoding information in single photons provides a way to test the secrecy of optical communications and distribute secure digital cryptographic keys. Beyond single photons, QDs can also emit entangled photon pairs, for instance through the well known biexciton–exciton cascade [1].

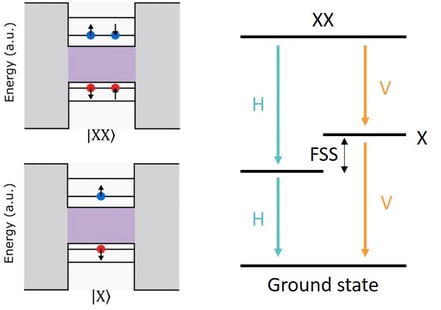

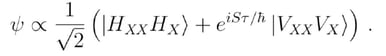

In this process, a QD initially contains two electrons and two holes, forming a biexciton (XX) state. Selection rules prevent a direct decay to the ground state; instead, the biexciton decays to a neutral exciton (X) state, which subsequently relaxes to the ground state. Due to spin conservation in the intermediate exciton state, two indistinguishable decay paths exist, each involving the emission of two photons with orthogonal polarizations. When these paths are equally probable, the resulting photon pair forms a polarization entangled state in the form:

While polarization entanglement is the most widely demonstrated and experimentally accessible form of entanglement in QDs, other types of entanglement such as time-bin, path, or energy-time are also possible. These entangled photons can be transmitted through optical fibres, serving as ideal flying qubits for quantum networking. But entangled photon pairs are only part of the picture. The vision of a quantum internet involves stationary qubit, used for memory and processing at spatially separated node, and flying qubits, which connect these nodes. QDs naturally support this dual functionality. By engineering the emission process, it is possible to entangle an emitted photon with the spin of an electron or hole left behind in the QD [2, 3]. With appropriate isolation techniques, these spins can retain quantum coherence over extended periods, effectively functioning as stationary qubits. This creates a hybrid quantum system in which the QD acts as a quantum node: it emits a flying qubit (the photon) while retaining a stationary qubit (the spin). If the photon is sent through a fibre to a remote receiver and detected there, the spin in the original dot remains entangled with the remote system. This functionality supports two key use cases:

Quantum interconnects: connecting nearby nodes, such as within a quantum data centre

Quantum communication networks: connecting nodes over long distances, where telecom wavelength operation is essential

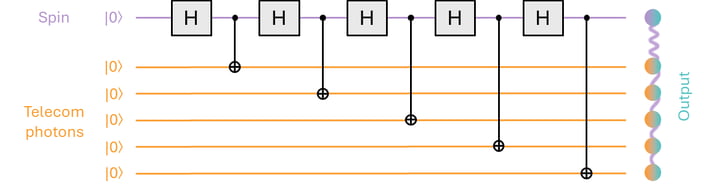

In both scenarios, the ability to entangle light and matter and preserve that entanglement during transmission makes QDs a powerful candidate for scalable quantum architectures. Taking this concept further, certain protocols enable the generation of a sequence of entangled photons from a single spin in a QD. By applying a series of precisely timed laser pulses and exercising coherent control over the spin state, it is possible to repeatedly entangle new photons with the same resident spin. A widely studied example [4] involves alternating operations that are functionally equivalent to Hadamard and controlled-NOT (CNOT) gates on the spin. As this process repeats, each emitted photon becomes entangled with the spin and, indirectly, with the previously emitted photons. After several cycles, a string of entangled photons is formed. Once the spin is disentangled at the end of the protocol, the string becomes effectively a one-dimensional all-photonic entangled state.

This protocol has already been applied to short wavelength QDs [5,6], where laser excitation pulses act as CNOT gates entangling the spin with an emitted photon, while spin rotations in a magnetic field implement Hadamard gates. A recent work [7] extends this approach to a telecom wavelength QD, generating multi qubit entanglement with direct photon emission in the telecom C band. Looking ahead, strings of entangled photons produced using this method can be connected into larger, multi-dimensional structures known as cluster states. These complex entangled states are a foundational resource for both quantum communication and quantum computing. In quantum networks, cluster states are central to building memoryless quantum repeaters, devices that help transmit quantum information over long distances. Much like signal amplifiers in today’s internet, these repeaters extend quantum communication links without needing to store quantum information along the way. This avoids the technical challenge of long-lived quantum memories and makes the system easier to scale.

Beyond networking, cluster states are also the foundation of measurement-based quantum computing. Instead of performing complex operations directly on qubits during the computation, this model begins with a pre prepared cluster state and carries out the computation by measuring these photons in a specific order and basis. Each measurement steers the outcome of the computation, effectively programming the result as it proceeds. This approach simplifies hardware requirements by shifting complexity to the initial entanglement step, making it especially appealing for photonic quantum processors where fast and flexible measurement is easier than gate-based control.

Refererences

[1] Stevenson et al. A semiconductor source of triggered entangled photon pairs. Nature 439, 179–182 (2006).

[2] Gao et al. Observation of entanglement between a quantum dot spin and a single photon. Nature 491, 426–430 (2012).

[3] Laccotripes et al. Spin-photon entanglement with direct photon emission in the telecom C-band. Nat Commun 15, 9740 (2024).

[4] Lindner, N. H. & Rudolph, T. Proposal for pulsed on-demand sources of photonic cluster state strings. Physical Review Letters 103, 113602 (2009).

[5] Cogan et al. Deterministic generation of indistinguishable photons in a cluster state. Nature Photonics 17, 324–329 (2023).

[6] Coste et al. High-rate entanglement between a semiconductor spin and indistinguishable photons. Nature Photonics 17, 582–587 (2023).

[7] Laccotripes et al. An entangled photon source for the telecom C-band based on a semiconductor-confined spin. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2507.01648 (2025)

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my employer or any organisation I am affiliated with.